Adelaide Motorcycle Centre

Motorcycle Experts

Adelaide Motorcycle Centre

Motorcycle Experts

Adventure Motorcycling

-

Into the Great Empty

Published in: Rides

There’s an undeniable mystique to the American West. Cowboys, Indians, outlaws and the Gold Rush—they all call as loudly as the wide open landscape itself. Inspired by our friend and Backcountry Bywaysauthor, Tony Huegel, and the custom routing he was working on for one of his adventure riding motorcycle clients, we decided to build a trip around this magnificently desolate place he refers to as “The Great Empty.”

It’s the big area of “nothingness” south of Lander, Wyoming, and north of Interstate 80, where there are very few roads and even fewer people. Originally from the east coast and now living in Idaho Falls, we have become increasingly enchanted with the western way of life and all the places to escape into the wilderness. With a newly purchased KTM 950 Adventure in the garage alongside my partner Edward’s KTM Super Enduro, the pull of the wide open west was too much for either of us to deny.

After months of Edward’s obsessive planning, we headed out of Idaho Falls on I-15 for about 40 miles. Exiting the highway at Mud Lake, we went north, taking some nice double track over Bannack Pass and crossing into Montana. We rode in a northerly direction for several hours, through miles of open range, leaving civilization farther and farther behind.

Medicine Lodge Creek Road brought us to Bannack State Park, the site of Montana’s first major gold discovery in 1862. The town was named after the local tribe of Bannock Indians, and swelled to around 10,000 people in its heyday. Bannack was also the capital of the Wyoming Territory for a brief period of time.

Once gold was discovered in nearby Virginia City, the population slowly dwindled until the last of the residents moved out in the 1970s. Now a National Historic Landmark with over 60 buildings, Bannack State Park is the best preserved of all of Montana’s ghost towns.

After nearly an entire day of solitude on the gravel roads, the number of tourists at the State Park was a jolt. When we were told that the fee was $22 to camp among barking dogs and belching RVs, we consulted the GPS and found a remote place on public land where we dry camped, sharing the last of the afternoon shade with a group of friendly cows.

Note in Edward’s journal: “No cars for hours. Chicken fajitas and three beers for dinner. Good start to the trip.”

We were at elevation and it was a cold night. Edward’s Super Enduro had trouble starting, so we rolled our bikes into the sunshine and waited. A while later everything had warmed up enough to kick over the engines and we rode out. With a huge hot breakfast in Dillon, Montana, we then headed for the Gravelly Range.

In the Gravellies, being virtually roadless means that what few roadways there are take your breath away. There’s a high elevation drive along the crest, with undulating mountain views on either side for miles. Part of the Beaverhead-Deerlodge National Forest, there are no services once you leave the highway, which suited us just fine with our inclination towards the wild and the remote.

The gravel road was easy and unchallenging, so it was effortless to focus on the alpine vistas, open foothills and coniferous forests interspersed with mountain meadows. We found ourselves riding separately yet together, each enchanted with the scenery. Later, I read that there are well over 250 species of wildflowers, grasses, shrubs, and trees occurring along the route. Even though the blooming starts in late June and runs through July, it was spectacular even in early September.

We spent most of the day under the enchantment of the Gravellies and considered camping there, but given our KTMs’ objections to the cold that morning, we knew that at 9000-plus feet of elevation we’d waste the next day’s precious riding time waiting for the mountain chill to recede.

Instead, we rode down to a campsite Edward knew in Red Rock Lakes National Wildlife Refuge. Spectacular in its own right, my only hesitation was the abandoned horse trailer with a multiplicity of printed admonitions to use it for food storage in case of bears.

Note in Edward’s journal: “Gravelly Range Loop was AWESOME! We must come back.”

We awoke to the serenade of trumpeter swans at dawn and ate our blissfully-unmolested-by-bears breakfast in camp overlooking the lake. Shortly after riding out we left the gravel roads and covered some ground along a section of the John D. Rockefeller Parkway, which connects Grand Teton National Park to Yellowstone National Park. Stopping for lunch at a picnic area, Edward braved the frigid waters of the Snake River for a bath. I refused.

Back on gravel, we rode over Union Pass at 9,300 feet. I was getting tired and making more riding mistakes than I cared for; however, it seemed to take forever to find a suitable camping spot that wasn’t private farmland. I stopped a passing pickup truck to ask a local where to camp, and he directed us to a spot on his land along the river, with a firm admonition to be on the look out for bears. Did I mention I have a thing about camping in bear country?

While discussing bear stalking and feeding theories, and what path a bear might take while crossing the river into our camp, Edward eventually walked away and started making dinner. He left me to put up the tent. When I was finished to the best of my bear-phobic satisfaction, I brought my chair over to the dirt area where he’d unpacked the stove and was boiling water for a dehydrated camping meal.

“Is that smoke?” I asked looking over his shoulder. He turned towards where I was looking and, as if time stood still, we both sat stupefied, seeing the black smoke of wildfire on the other side of the closest range of hills. We looked at each other and nodded simultaneously; with silent agreement we abandoned dinner, packed up camp and moved on.

Several hours of riding in the dark later, we passed through Pinedale, Wyoming. We navigated out of town to a remote spot Edward remembered from a previous trip. We set up the tent like robots using our head lamps to guide our actions, and crashed into our sleeping bags without eating.

Riding Lander Pass we were on gravel roads once again when we encountered a dirt and rain storm. The violent winds of a dark storm that the western states seem to brew up so easily was tossing the freshly graveled surface into the sky. Somehow we made it to the Lander Cutoff Road.

As the sky cleared, we found ourselves at a famous landmark -- the intersection of the Oregon Trail, California Trail, Mormon Trail and the Pony Express, before departing on the Oregon Trail through a whole lot of empty landscape.

Despite being used by 400,000 settlers migrating west across the United States, the Oregon Trail was difficult to ride. Two deep trenches, the width of wagon wheels, remain as a reminder of how difficult it was for settlers to travel through the harsh and inhospitable terrain. Riding our big bikes in the cavernous ruts was a workout.

The next day we came to South Pass City, the site of Wyoming’s biggest gold boom and bust. A lonely, windswept graveyard stood above town. The South Pass City State Historic Site preserves more than 30 historic structures, and the Continental Divide National Scenic Trail also passes through town. With a population of about seven people, “town,” is a stretch of the term—we didn’t expect to find any services there.

The Carissa Mine stands just beyond town, an immense structure which permanently ceased operations in 1954. The state of Wyoming purchased the Carissa in 2003, and has financed a massive renovation, including re-purchasing several essential pieces of equipment previously sold off. The Carissa can now be toured Memorial Day through Labor Day, but we were too late in the season.

In Atlantic City, Wyoming, we were drawn into the Atlantic City Mercantile, where history is alive in the décor as well as the preserved building itself. Atlantic City, with its 37 residents, is a metropolis compared to South Pass City. We left the friendly locals and decided to push on because we were now on the edge of the Great Empty—the crown jewel of this trip.

In Atlantic City, Wyoming, we were drawn into the Atlantic City Mercantile, where history is alive in the décor as well as the preserved building itself. Atlantic City, with its 37 residents, is a metropolis compared to South Pass City. We left the friendly locals and decided to push on because we were now on the edge of the Great Empty—the crown jewel of this trip.Note in Edward’s journal: “Nice morning. Many hours of the Great Empty. Great Riding.”

There were no houses. No ranches. Only endless horizon and little-used roadbed. According to the GPS, the nearest highway was over 60 miles away. We passed a sign for the Sweetwater Uranium mine, of all things, and knew we were beyond nowhere.

There wasn’t another soul around; the only vestige of humanity an abandoned and derelict settlement where a hardy soul had once tried to make a go of it in this harsh and unforgiving environment. Even when expecting a vast, empty plain, we were astonished at the desolation of this part of southwestern Wyoming.

In many places there was no visible life—not even the normally ubiquitous sagebrush. Just mile after mile of wide open road, fascinatingly empty landscape and nothing but the noise of the wind for company. We pressed on; knowing that if needed, it was doubtful there would be any salvation.

Note in Edward’s journal: “‘Holy Crap... I hope this goes through,’ was all I could think today. I’m glad I did my research.”

Eventually the formidable landscape gave way to low scrub and cow country and we came to a small stream where things were slightly greener and a little more forgiving. We found the bovine companionship gathered around the small patch of green reassuring company after all that great empty space, enough so that we decided to stop for the night.

The next morning we packed up and left our little oasis, setting out through the Great Empty yet again. The sun beat down, the road stretched on long and straight, and the dust plume behind us went on and on, lingering in the air long after the roar of our KTMs melted into the horizon.

Helpful Resources:

• Backcountry Byways Custom Trip Routing

Tony Huegel

• Bannack State Park

721 Bannack Rd

Dillon, MT 59725

Latitude/Longitude: (45.16212 / -112.99868)

Open year round

Fall/Spring: 8 am–5 pm

Summer: 8 am–9 pm

• South Pass City and Carissa Mine

• Benchmark Maps

Read more... -

Arizona Backcountry Discovery Route

Published in: Rides

From seeing the Colorado Backcountry Discovery Route in a movie theater, to becoming one of the characters in the next BDR, Inna Thorn brings you this engaging, behind-the-scenes report of her off-pavement motorcycle adventure through Arizona’s backcountry.

• How it all Started

As I sat in the theater at the Colorado Backcountry Discovery Route movie premiere, watching a group of guys having the time of their lives riding adventure motorcycles in the majestic Colorado high country, I suddenly realized how much I missed experiencing the world on two wheels.

In 2008, my boyfriend and I quit our jobs and set off on a motorcycle adventure from Seattle to Ushuaia. For six months we tasted the world, mile by mile, as we traveled aboard our Kawasaki KLR 650s. Riding about 20,000 miles, we crossed 13 countries exploring some of the most remote and legendary places in the Southern hemisphere. Something inside us changed on that trip—we had the adventure bug.

A lot has happened since. We got married. My passion for adventure motorcycling guided my career, and I joined Touratech-USA. In 2011 our son was born. Motherhood and parenting consumed my life. Coming out of a year-long maternity leave, I welcomed the opportunity to work for the Backcountry Discovery Routes (BDR) as manager of the non-profit organization. The organization’s goal is to provide resources and inspire people to explore the backcountry by motorcycle.

That evening the COBDR movie reawakened my yearning for adventure. Motherhood aside, life on the road seemed so alluring again, but was it realistic? During the question and answer period afterwards, I asked if they’d consider having a woman in the next film? A week later, I was invited to join the BDR scouting team for the Arizona BDR documentary.

• Preparation Time

The report from Rob Watt who’d been scouting the route for the last two years sounded a bit unnerving. AZBDR is the most remote of the BDRs so far. We would camp for the entire nine-day expedition, encounter sand, steep hills with loose rock, and long days in remote areas. We would also have to watch out for cactus, snakes, scorpions, and something called the Valley Fever.

With just over a month to prepare, I took a dirt training class with PSSOR (Puget Sound Safety Off-Road). It made me realize that my trusty KLR 650 might be a bit too much bike to handle in the rugged terrain. A good friend graciously offered his ADV-ready Yamaha WR250R for the expedition. Another weekend-long practice in the dirt on the WR and I was ready as I could be. It was finally travel time!

• The Team

We met at GOAZ Motorcycles in Scottsdale, AZ, for final preparations. The group consisted of dual-sport enthusiasts from across the motorcycle industry. Tom Myers and Paul Guillien of Touratech-USA; Justin Bradshaw of Butler Motorcycle Maps; Rob Watt, owner of Trailmaster Adventures; Florian Neuhauser, editor at Road Runner Magazine; Austin Vince, the gregarious British adventurer and filmmaker; Jon Beck, photographer; Sterling Noren, filmmaker; and me.

• The Border

The Coronado National Memorial, commemorating the first organized expedition into the Southwest by conquistador Francisco Vásquez de Coronado, also marked the beginning of the AZBDR expedition. Dusty twisties led up to the entrance of the Coronado National Forest on the southeast flank of the Huachuca Mountains.

From there we could see deep into Mexico, including the border guard surveillance activities. We rode along a welded steel fence that marks the Arizona/Mexico border, a popular drug smuggling route in the Southwest. Despite the warnings we hear on the news of “Just don’t go near the border,” we never felt in danger, and encountered a number of friendly border patrol agents who just waved as we rolled by.

• Tough Terrain

The following day epitomized difficult terrain as we rolled out of camp and immediately hit soft, deep sand. I couldn’t gain much speed, my front wheel kept catching on the ruts and the bike kept going wherever it wanted. By the time this sandy section was finally over, I’d had at least four falls, was overheated and completely worn out.

The sand gave way to steep hills carpeted with loose rock where Sterling set up a shot at the top of a curvy hill. We were to ride up one bike at a time as the camera rolled. I watched other riders skillfully muscle their large bikes up the hill. I said my prayers before tackling the challenge and starting the climb. When I made it to the top of the hill I reveled in the feeling of triumph.

A few minutes from reaching pavement, Austin took a nasty fall and seriously injured his knee. Just like that his trip was over and we were forced to say goodbye. It was a bittersweet ending to an otherwise victorious day.

We awoke the next day in a cozy bowl of a valley, with towering saguaro cactus in full bloom painting the hills. The riding started out easy on a wide, hard-packed dirt road. After a quick fuel stop, we rode alongside old train tracks. The road was rutty but fun and fast-paced, the kind the WR is made for. I had a couple of scary moments, but managed and kept the momentum going with a huge smile on my face.

We crossed the Pioneer Pass at 5,900 feet and drank in the stunning high country scenery and lake views. It was BDR at its best.

• Putting the Backcountry in BDR

We entered the Sierra Ancha Wilderness of the Tonto National Forest. The road weaved in and out of the forest, opening to spectacular views of precipitous box canyons, high cliffs, and pine-covered mountains. The path was hard pan with jagged rocks for hours on end. Difficult riding and the heat of the sun quickly diminished our water supplies.

After another tire-changing break, we took a turn and descended on the twisty, rocky, slippery road that would be marked “Expert” in the final AZBDR route. It was a physical ride, but on my WR250 I just cruised down in first gear, dancing the bike around the big rocks.

By the end of the day everyone was completely exhausted, out of water and food, and low on gas. Finally at the campsite, we washed clothes in the creek, and gathered around the campfire for a five-star dinner and drinks.

• Mother’s Day

When I became a mom two years ago, I never dreamed I’d spend Mother’s Day 1,000 miles away from my baby, camping in the wilderness with a bunch of men. I woke up to the chirping of birds and the smell of coffee and the guys making me Mother’s Day breakfast.

It was an enjoyable and scenic day of riding. We were treated to iconic views of the plateau country and desert canyon country from the rugged Mogollon Rim, an escarpment that forms the southern limit of the Colorado Plateau. It drops as much as 2,000 feet in some areas and provides some of the most far-reaching scenery in Arizona.

On the fast gravel road we zoomed through the diverse landscapes of the Coconino National Forest, with its ponderosa pine forests, mesas, alpine tundra and ancient volcanic peaks, then continued to the Long Lake for photos. A rocky road through the bushy terrain resulted in more flat tires. Most of us ran out of water and food, a testament to the remoteness of the ABZDR.

In the morning we rode through black volcanic sand. I was intimidated at first but quickly got the hang of it, and then, no one could stop me. I was zooming pass the guys, jumping over the road humps feeling like a motocross rider.

• Grand Canyon and the Navajo Nation

We made a quick tourist stop at the Grand Canyon before heading to our next destination—the Navajo Nation. As we entered the large expanse of the Navajo land, with its spectacular canyon mesa scenery, the land felt venerable and sacred. A herd of wild horses ran off in the distance.

Rob had a very special cliff-side camping spot for us that night—right on top of the deep and jagged Little Colorado River Canyon. It had the most spectacular views of any site I’d ever seen. We pulled up to the edge to set up camp. The sandy soil made it hard to keep the tents staked down. Some brave guys even placed their tents just a bike length away from the canyon’s edge.

• Rough Night

As darkness fell, the wind grew stronger. By the time we were crawling into bed, the wind was beginning to blow our personal effects away. As the gusts became more intense, I feared my tent was going to lift up and fly away along with my helmet, my riding boots and my bike into the deep drop of the canyon. The wind was relentless. Blood-shot eyes told the story the next morning. No one slept a wink, and we were all wandering around looking for missing belongings.

Rob had another special surprise for us that morning, a view point of the Grand Canyon accessible by a secret track not easily found on the map. Our group took in the dramatic views of a place most people have never seen—a perfect ending to our Grand Arizona Adventure.

• Gift of the BDR

For many people, adventure travel means going to faraway places on the other side of the world, taking months off work, investing hours into planning. The gift of the BDR is the reminder that unique adventures are much more accessible than we may realize. Right here in our backyard are beautiful places for motorcycle riding. The routes are established and the GPS tracks are free. In less than a week’s time you can have memories that will last a lifetime.

Experiencing Arizona by remote backroads on two wheels gave me a new appreciation for its natural beauty and its iconic landscapes. On a personal level, AZBDR was a tale of a Hero’s Journey: the call to adventure, the doubting of my abilities, the support and camaraderie of the team, the tests, challenges and tribulations, the rewards and the final triumphant homecoming.

AZBDR made me face my fears, and instead of dreading the sand or the rocks, I learned to conquer them head on. Apart from experiencing the beauty of the world, for me, this personal growth is my favorite element of adventure motorcycling.

Read more... -

EICMA 2025 New Bikes and Old Brand Revivals

Published in: News

EICMA 2025 made one thing clear: the future of motorcycling is leaning hard on its past. From BMW’s long-awaited F 450 GS and Royal Enfield’s evolved Himalayan lineup to the rebirth of British and Italian icons like Norton, BSA, Moto Morini, and Aprilia, the show floor was filled with adventure and dual-sport machines that fuse modern engineering with familiar, time-honored badges.

EICMA isn’t just a place for motorcycle brands to show their latest products – it is a global stage that showcases the future of performance, design, and innovation under a single roof. Like every year, launches and reveals were aplenty at this year’s Milan event, but one thing stood out: the resurrection of brands and motorcycles, especially in the adventure bike category.

Come to think of it, this makes a lot of sense. As markets mature and riders grow nostalgic, there’s a renewed appetite for machines that blend modern performance with old-school soul. This year’s show captured that spirit perfectly, and it wasn’t just through retro styling; there was a lot more to it.

BMW’s mini GS leads the charge -• BMW F 450 GS: A Lightweight Adventure Bike With Dakar DNA

Leading the way was BMW Motorrad, which unveiled the long-awaited F 450 GS. For years, BMW’s adventure lineup has been dominated by the heavyweight R 1250 GS (recently replaced by the 1300) and the midsize 800 and 900 series, but the 450 brings the brand back into a segment it helped define decades ago — lightweight, rally-bred adventure bikes designed to be ridden hard and far.

The bike is set to be produced by India’s TVS Motor, the same manufacturer that worked on BMW’s G 310 models. That includes the engine too – an all-new 420cc parallel-twin producing 48 horsepower and 32 lb-ft of torque. All that power should feel even punchier considering the F 450 GS weighs 393 lb, compared with the Himalayan 450’s 432 lb and the Ibex 450’s 430 lb wet weight.

Compact, punchy, and unmistakably GS, the new model signals a strategic push toward younger riders and emerging markets, where accessibility and versatility matter as much as badge value. The best part about the F 450 GS is that it serves as a subtle nod to BMW’s Paris-Dakar-winning history. The only real question is when it will make its way to the USA.

• Royal Enfield Himalayan Rally 450 and 750: Evolving an Adventure Icon

If BMW represents heritage reinterpreted, Royal Enfield embodies heritage refined. The Indian manufacturer has spent the past decade methodically modernizing its lineup without losing its vintage charm. At EICMA, Enfield took another bold step by unveiling the Himalayan Rally 450 (packaged as the Himalayan 450 Mana Black) and offering a glimpse of the much-talked-about Himalayan 750.Both bikes speak to the brand’s deep connection with long-distance exploration. The 450 Mana Black edition boasts a matte black colour scheme with rally accessories, including a high-set, beak-style fender, flat bench-style seat, knuckle guards, and a rally-style rear panel as standard.

The 750 Himalayan, showcased as a “work in progress” model with limited details, is built around a 750cc motor. The engine looks very similar to RE’s 650 twin but will likely have a longer stroke than the 650cc unit. The bike itself appears to use an entirely new chassis with a revised headstock and a new subframe. Suspension consists of adjustable USD front forks and a monoshock, while the design remains unmistakably retro, carrying forward the same philosophy as the current Himalayan.

• Norton and BSA: Classic British Motorcycle Brands Return to the ADV Segment

Norton Motorcycles’ storied comeback under TVS Motor’s leadership continued with the introduction of an entirely new range of motorcycles, including the reintroduced Atlas and Atlas GT adventure models built around a 585cc inline-twin engine and Kayaba suspension.

The Atlas twins marry traditional British twin-cylinder aesthetics with cutting-edge engineering, combining sculpted tanks, upright geometry, and a distinct silhouette that recalls an era when motorcycles were both beautiful and brutal.

But Norton isn’t the only British brand scripting a revival. BSA Motorcycles unveiled its first adventure motorcycle, the Thunderbolt 334. Based on the Yezdi Adventure (sold in India), it’s a compact, approachable ADV that borrows styling cues from its 1960s namesake.

It’s powered by a liquid-cooled, 334cc single-cylinder engine that complies with Euro 5+ standards. The bike features three ABS modes — Rain, Road, and Off-Road — along with a six-speed transmission and traction control. There are also USD forks, a preload-adjustable rear monoshock, a slip-and-assist clutch, and a reinforced bash plate for use on varied terrain.

It’s a proper ADV that looks like it can take a beating and do it with a lot of charm. Where the original Thunderbolt was a symbol of post-war performance, the modern version embodies small-bore practicality and classic design sensibility — a reminder that heritage doesn’t have to mean high displacement.

• Moto Morini and Aprilia: Expanding Italy's ADV Lineup

Next up on the revival bandwagon are the Italian brands. First is Moto Morini, which revealed its all-new single-cylinder Kanguro enduro. For those who might not know, the name dates back to the 1980s, when it belonged to a practical dual-sport that blended utility with Italian style.The 2025 version captures that same spirit, wrapped around a modern chassis and engine platform that makes it far more capable than its predecessor. Its 300cc single-cylinder produces 34 horsepower and 20 lb-ft of torque, making it suitable even for A2 license holders.

The enduro is built on a steel frame with an aluminum swingarm, a 41 mm front fork, and a rear shock absorber with progressive linkage, offering 9.8 inches of wheel travel. ABS is switchable, and Moto Morini is even offering a Rally version, which features a low fender and a compact windshield.

Then there’s Aprilia, which plans to expand its adventure range with the Tuareg 457, effectively democratizing the revered Tuareg nameplate. While Aprilia has yet to formally reveal the bike, there have been multiple sightings, most recently in Tunisia. It will likely share the RS 457’s engine, which produces 47.6 horsepower, and is expected to feature a 7.9-gallon fuel tank and a dry weight of 353 lb.

• Why the Revival Trend Makes Sense

As EICMA wrapped up, it felt as though the motorcycle industry had come full circle. After years of chasing bigger engines and ever more complex tech, manufacturers now seem to be turning toward simple, soulful motorcycles that prioritize accessibility above all else.So why the sudden wave of revivals? The answer lies in a mix of emotion and economics. In an increasingly digitized, electric, and efficiency-driven world, motorcycles remain one of the few products powered as much by feeling as by function. Manufacturers have realized that tapping into their history doesn’t just appeal to older enthusiasts — it also resonates with younger riders searching for authenticity in a sea of increasingly tech-heavy machines. Also, we' continue to see legacy defunkt brands, which have been kicked around for decades, now being bought and revived by Asian mannufacturers looking to bring excitement and value to the motorcycle market.

There’s also a clear business logic. Reviving a dormant nameplate carries less risk than inventing a new one. Heritage gives brands the advantage of instant recognition, while modern engineering ensures performance and compliance with global standards. It’s a win-win that allows companies to grow without losing their identity.

And if this year’s EICMA is any indication, the past isn’t just returning — it’s accelerating toward the future, throttle wide open.

Read more... -

UK to Cape Town: 40,000 km Ride 2-Up Beating the Odds

Published in: Rides

I sit here writing from an Airbnb in Cape Town, South Africa, somewhat in disbelief that my fiancé and I have traveled here not by plane or boat, but overland on a motorcycle. We rode out of a sleepy village in the U.K. 283 days ago with everything we’d need piled on the back of our BMW R1200GSA. An adventure that would take us over 41,000 km through 30 countries and across three continents.

Why the disbelief? Rewinding the timeline just over a year, I had no motorcycle, no motorcycle license, no riding or camping gear, and neither of us had any adventure motorcycle travel experience whatsoever. From there, we didn’t start a story of calm, easy travel on smooth tarmac roads; we were destined for true adventure. We rode some of the most challenging roads in the world, crashed in Albania, were escorted by the Iraqi military, overcame a multitude of logistical nightmares, crossed crocodile-infested rivers in the middle of the Zambian jungle, camped with tribes and rhinos, and much more.

I did have some motorcycling background. My dad, a keen biker back in the day, had me riding a 50cc Honda Monkey around the yard as a wee lad. That ignited a flame; I quickly developed a passion for anything on two wheels, spending much of my teenage years racing downhill mountain bikes and modified pit bikes.

On the other hand, Lucie had absolutely no motorcycle experience and not much interest. She had the sadly-too-common story of a motorcycle-related death in the family. Her parents remained in denial about our adventure plans until the day we wobbled up outside their home on the imposing R1200GSA. I didn’t help matters when I accidentally dropped it on their car!

Our inspiration will come as no surprise—watching Charley and Ewan on the Long Way series. As a young lad with a passion for motorcycles and a developing interest in travel, seeing that one could ride around the world on a motorcycle… well, it was one of the coolest things imaginable. But it wasn’t until we rewatched the series a few years ago, while serendipitously planning a sabbatical to travel the world, that the mental gears started turning… “Could we travel by motorcycle?” It was a thought that led down a rabbit hole of researching all things related to adventure motorcycle travel. Before long, a plan took form. We had a rough idea of a route, booked training, and eventually obtained a motorcycle license, found a suitable bike, ordered everything we’d need, and eagerly began preparing for the trip of a lifetime.

We hadn’t planned everything perfectly, though. The first time we loaded the motorcycle was the morning we left. I couldn’t believe how heavy it was… it felt like the sidestand had been welded to the ground. But thankfully, once the mighty GS got rolling, the awkwardness all but disappeared. It was easy to maneuver and very comfortable.

After some sad and somewhat concerned farewells from family and friends, we set off for the channel tunnel. The first month was spent acclimatizing to this new way of life, figuring out our gear, cautiously trying to wild camp, finding our roles, and gradually building confidence on the BMW. Eager to reach further afield, we crossed five borders in five days to arrive in Switzerland. Over the following weeks, we meandered through the Alps, crossed northern Italy to Slovenia, then followed the Adriatic coastline to Greece, where we turned inland to head east through Turkiye.

One of our big targets was the infamous Pamir Highway in Central Asia. But upon reaching Georgia, we learned the Azerbaijan border was closed indefinitely. After exhausting all the options, we reluctantly accepted that our Pamir dream was over. It seemed the universe had different plans for us. In Armenia with no feasible way of continuing east, we were left with a choice: return to Europe or turn south, through Iraq. We chose Iraq.

The experience that unfolded during our time in the beautiful desert country was one of total and complete wonderment, kindness, openness, adventure, and selfless hospitality free from expectation. We could write several articles about this alone! Our journey through this lesser-traveled part of the world demonstrated the stark difference that can exist between images and words used by the media and the actual reality of the people and culture. We were shown hospitality, kindness, and love on a whole new level. It completely took us by surprise.

Following an unforgettable time riding through Iraq, we reached Jordan and continued on to Saudi Arabia, where we took a ship across the Red Sea from Jeddah to Port Sudan, our gateway to Africa. With a warm welcome from the Sudanese bikers, we rode through the country with an open heart and open mind, despite the country’s reputation and history of unrest.

Days before we planned to leave Khartoum, the capital of Sudan, to ride to the Ethiopian border, we heard news of an overlander stuck at the border due to a change in the law. Ethiopian customs now demanded a cash bond/deposit of many multiples of a vehicle’s value. Again, it seemed the universe had different plans for our trip. After weeks of research, deliberation, and discussions with other travelers and locals, we decided to airfreight our bike to Kenya. At $4,000 including our own flights, this pushed us way over budget, but the only other option was to end the trip and fly home. We’d just landed in Africa with our sights set firmly on reaching Cape Town, and we were not ready to give up.

After finally clearing the BMW through Kenyan customs and reassembling it at the campsite, the journey continued. We spent a couple of weeks exploring Kenya and relaxing by the Indian Ocean before turning south once more to cross through Tanzania and Malawi, then west through Zambia, Zimbabwe, Botswana, and Namibia where we reached the west coast, the Atlantic Ocean. Namibia was an absolute dream for adventure motorcycling and quickly became one of our favorite countries where we enjoyed a month of exploring remote areas off-road, getting stuck in the sand, wild camping with rhinos, and meeting so many amazing people.

Click here to read "Riding Africa's Wild West: A Namibian Adventure"

Then it was on to our final country, number 30, South Africa. Not wanting the trip to end, we explored the Western Cape and took our time slowly working towards Cape Town, where we eventually, and reluctantly, finished the trip at the Cape of Good Hope, the most southwestern point of Africa.

Then it was on to our final country, number 30, South Africa. Not wanting the trip to end, we explored the Western Cape and took our time slowly working towards Cape Town, where we eventually, and reluctantly, finished the trip at the Cape of Good Hope, the most southwestern point of Africa.

It’s funny how this lifestyle became so normal to us. After nine months on the road and more than 40,000 km since we left home with shiny new equipment and no experience, the day-to-day adventure motorcycle travel had now become our life, our routine, our normal. It has taught us that we (that means you, as well) are capable of so much more than we ever assumed. All it took was to believe in ourselves and get out there and do it, making mistakes and learning as we went. It’s truly amazing what can be achieved by simply taking one day at a time—when, before you realize it, you might find yourself on the other side of the planet!

The Pillion Perspective

When Matt brought up the idea of doing this trip, I had a lot of questions. At that time, we’d only had a bit of experience riding two-up on mopeds in Thailand and Indonesia. That was a great way to see areas of a country one may not otherwise visit, but it was a long way from an RTW on a GS! At the time, Matt didn’t have a motorcycle license and had never even touched a big adventure bike. But as we further researched and the planning came together, discussions of traveling by motorcycle became more normal.

I was always quite comfortable riding pillion. Being smaller folk, we had plenty of space on the big GSA and I would sit with my hands in my lap—and Matt often said that he didn’t even notice I was there. But then we had our first serious fall in Albania which ended up with me spending a night in the hospital. Our confidence went from leaning over and scraping the pegs around corners, to slowing way down and riding with caution on twisty roads. We slowly regained our confidence and again began enjoying the twisty mountain roads.

My favorite part of motorcycling is off-road riding. I love the challenge and working together as a team. Many ask, “Do you stand up?”—of course I do! I think the riding would be very hard for Matt if I didn’t and it would feel like I was being dragged around without helping at all. I stand when Matt does and sometimes even without him. In the beginning, we communicated a lot when we stood up and sat down, but eventually you learn to read the road and know when it’s necessary. The back end moves a lot more freely when I’m standing and moving my weight around. You learn the bike’s limits, and feel when it’s tipping too much. Eventually, I was really helping to prevent the bike from falling over on those rocky or sandy tracks.

Matt Shieldsand Lucie Vivian are a British couple with a thirst for adventure travel. While they enjoy sipping cocktails on the terrace of a sunset villa in the Maldives, they get much more from straying off the beaten track and trying to avoid the tourists. You can follow their adventures on YouTube and Instagram @we.are.adventure.riders.

Matt Shieldsand Lucie Vivian are a British couple with a thirst for adventure travel. While they enjoy sipping cocktails on the terrace of a sunset villa in the Maldives, they get much more from straying off the beaten track and trying to avoid the tourists. You can follow their adventures on YouTube and Instagram @we.are.adventure.riders.

Read more... -

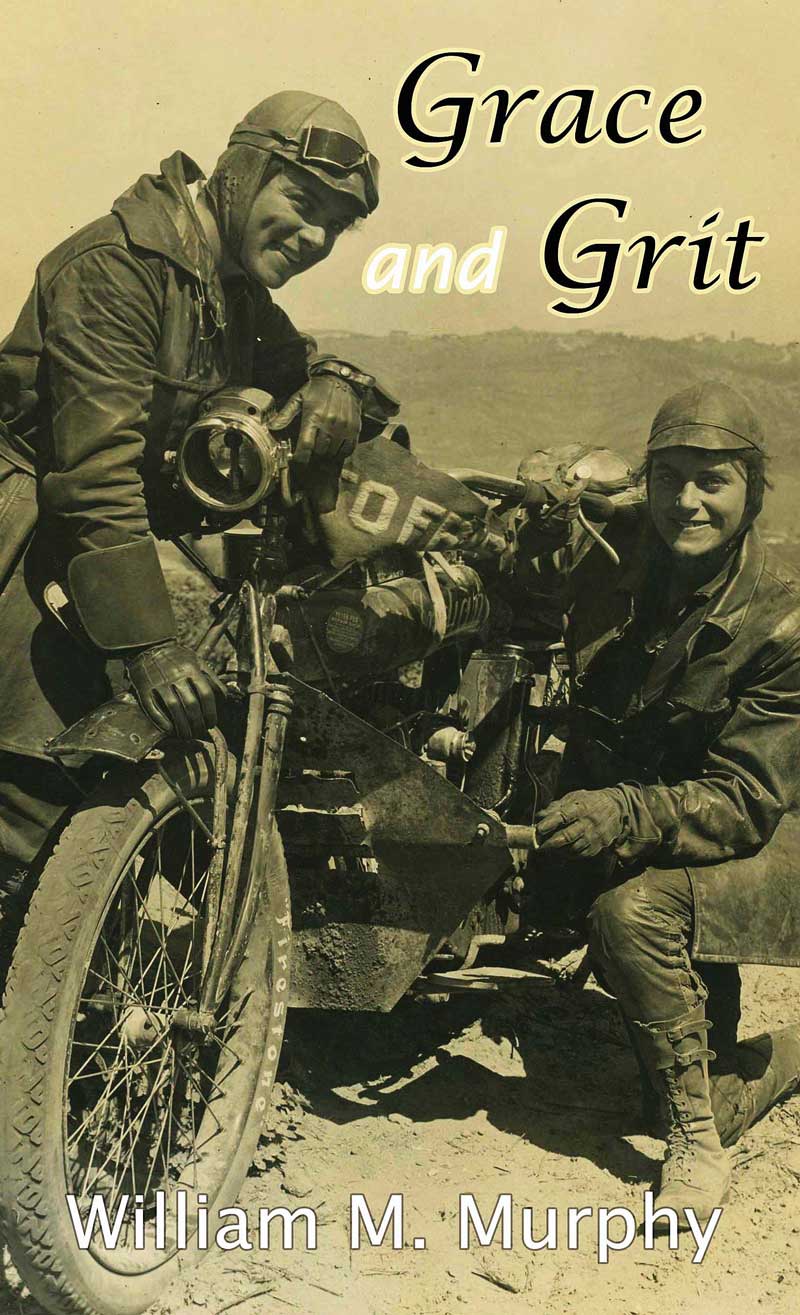

Book Review: Grace and Grit by William M. Murphy

Published in: Media

A Book about Motorcycle Dispatches from Early Twentieth Century Women Adventurers

Lost in the pitch black desert at night—no headlight, no moon, no sign of a trail. Slogging through heavy rainstorms and deep, sticky gumbo—washed out bridges and long detours. Negotiating mountain climbs with tortuous, narrow switchbacks where one false move meant a deadly fall….

It has all the makings of an epic adventure ride in some exotic locale, but this was the common experience in America 100 years ago for the few who dared cross the continent on motorcycles. In this case, a few intrepid women who defied the Victorian ideals of feminine behavior and became pioneers in the world of motorcycling.

Illuminating the state of transportation around the turn of the century, Grace and Grit is a well-documented and entertaining account. It tells the tales of Della Crewe, Effie and Avis Hotchkiss, and Adeline and August Van Buren, women who undertook nearly impossible journeys on “highways” which were little more than poorly marked, unimproved dirt roads and old stagecoach trails, on motorcycles that were temperamental, heavy, and difficult to operate.

Effie Hotchkiss made the difficult ride self-supported, with little fanfare and her 215-pound mother in a sidecar. Describing an incident on dirt roads in Iowa, she says, "The mud was thick and the road looked to have been stirred with a big spoon and then left to its fate, the stirring having brought up a lot of assorted rocks from the depths. I had not gone very far when the motorcycle and I took a header. This was quite humiliating as I had no inferiority complex when it came to my ability to handle a motorcycle. I was not hurt, who could be landing in the soft goo, but I cried from pure rage. I got on again and the road got worse, if that was possible, and I had another spill."

Hotchkiss and her contemporaries were capable and determined. The Van Buren sisters made their 1916 transcontinental ride as the U.S. wrestled with the question of entering World War I. They wanted to prove to the Army that women were capable of serving as dispatch riders, freeing up men for the front lines. In spite of their successful demonstration, the Army wasn't convinced, but the sisters' legacy endures. In fact, a cross-country ride in their honor is being organized to honor the centennial of their accomplishment.

I found Grace and Grit a great read and an inspiration. As author Murphy writes, “... we are the beneficiaries of everything gained by those who had the moxie to at least try, succeed or fail.” Knowing what these women accomplished, it would be difficult not to be motivated to honor them by spending more time on my own two wheels.

Title: Grace and Grit

Author: William M. Murphy

ISBN: 978-1-933926-40-7

Paperback: $17.70 | Kindle: $6.99

Publisher: Arbutus Press

Read more...